2020 Essay Contest Winner

The Wild Self

What is wild to one is home to another

by Lorraine Monteagut

For Bey, the wildest of them all

The doors to the world of the wild Self are few but precious. If you have a deep scar, that is a door, if you have an old, old story, that is a door. If you love the sky and the water so much you almost cannot bear it, that is a door. If you yearn for a deeper life, a full life, a sane life, that is a door.

—Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype

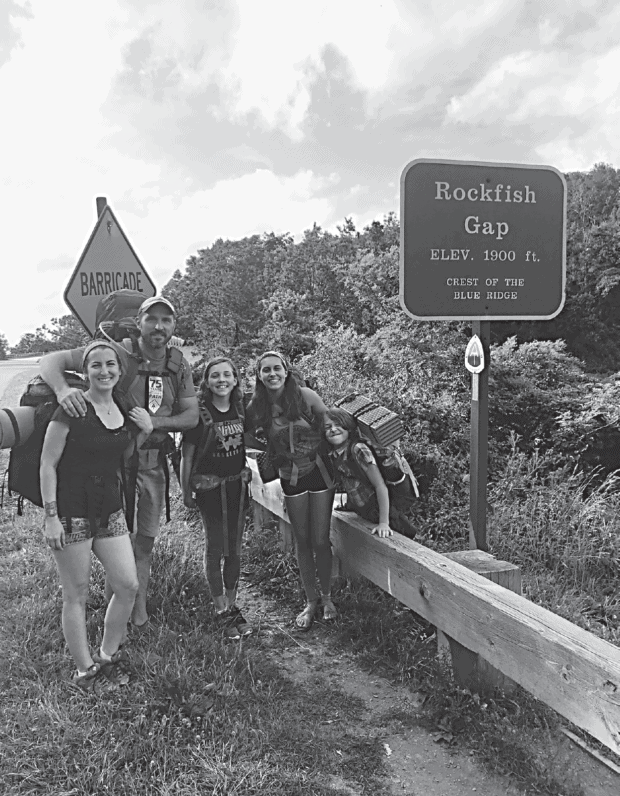

When we saw the radio towers, we hurried the rest of the way to the summit of Bear Den Mountain. We dropped our packs and took to the tractor seats jammed into the earth facing the Shenandoah Valley, partially visible through power line clearings. It was late June 2019. We were losing light on the first day of our 161-mile section hike of the Appalachian Trail north from Rockfish Gap. It was our first trip as a family: Ben, me, and his three kids. The previous summer, they’d hiked the section between Hot Springs and Springer Mountain. I’d never hiked more than 30 miles in one trip, and I was relieved to see signs of civilization.

We descended to Beagle Gap as the sun set and the clouds gathered. We passed through a grassy field littered with lightning bugs to the base of another mountain. We turned our headlamps on and climbed silently until we arrived at a meadow near the top. The next morning we would notice the marker for Little Calf Mountain and take in panoramic views of the Shenandoah National Park’s southern end and see for ourselves why the surrounding mountains are called Blue Ridge.

We barely made camp before the rain started. At the first thunderclap, the kids scrambled into their tent, and Ben and I dove into ours a few yards away. We yelled to each other as we unceremoniously downed our Clif bars. The lightning struck directly overhead. The tents flapped violently. Hours went by and we couldn’t sleep. Ben watched the Doppler on his phone, bands and bands of red moving over us. I could tell he was grappling with himself, trying to decide if there was anything we could do. I took the opportunity to let my worry show, too. But I wasn’t worried about the storm. I was suddenly nervous that I wouldn’t keep up on this hike, that I would never settle into this family, that maybe they preferred last summer when I wasn’t there.

That’s when I knew we’d arrived at the wilderness we’d been seeking. Or that it had somehow found us, some invisible frontier shifting over us in the storm, replacing our semblance of control with a primal vulnerability.

The frontier is defined as the border between settled land and wilderness, and it continues to be part of the American imagination even after we’ve staked everything out. In the mid-1700s the Shenandoah Valley was an important frontier of population migration. Migrants traveled from southeast Pennsylvania through the valleys south and west, through Maryland, to Virginia, and into the southern backcountry, many moving through Rockfish Gap, which featured one of two east–west roads. They were in search of cheap lands and fertile soil, of sustainable and safe homes. I imagine they thought themselves pioneers, never mind that the area had already been used as a war and trading route by the Cherokee and Iroquois for centuries.

At the top of Bear Den Mountain, these tractor seats face the Shenandoah Valley view.

Before our trip, I’d only read about the area or seen it in movies. It was an old America my family wasn’t a part of. I was raised in the extreme southeast corner of the country by newer immigrants, but our aim was the same. Settlement. Safety. Stability. Our frontier was the eastern edge of the Everglades, which we kept pushing against with our suburban homes. For a week in the mid-1990s, our house was the westernmost one among vast fields of strawberries, and I’d climb onto our roof to look out past the migrant workers picking, into the marshy wilderness even farther west, forbidden to me.

In most Latinx families, hiking is not a thing you do for fun. Walking just because? We’d walked when we were forced to leave our homes. We’d run from war, from military occupations. It was a wildness to which we did not want to return. Our assimilation called for domestication, especially for the female. My mami called me callejera and poured alcohol on my wounds when I came home scraped up, to teach me to stay inside. The next morning I was crawling out at first light, my hurt knees tender against the windowsill, on my way to adventure the borders of our growing civilization.

I didn’t realize then what a great privilege this was, to be outdoors willingly. I didn’t realize that my white skin afforded me opportunities that my darker cousins would never experience, that I could mimic the pastimes of the longer established Americans and nobody would think me uneducated as I made my way home covered in dirt.

We didn’t go on road trips to national parks, like in the movies. I dreamed of forests and mountains, but what I had was flat land. I walked out of my neighborhood and followed the road until it ended and I pushed west with my imagination, believing I was the first one to ever do so.

A wild little thing, my parents called me.

On the second day of our hike, as we entered the Shenandoah National Park, I stumbled over my feet on a descent, and my left knee landed on a sharp rock. I was in massive pain but tried not to show it, pushing back the thought that I might have to sit this trip out after all. I wouldn’t know until weeks later, but I’d torn the tendon just below the kneecap.

The section of the AT that runs through the park is a far cry from the frontier of the 1700s. The many areas that converge with Skyline Drive feature nice convenience stores and day-hikers who smell like dryer sheets, who park and walk to the nearby summits. A controlled wilderness, the valley glinting with human life.

As I limped around camp, Ben suggested I drive along Skyline and meet them each night at the campgrounds. The previous night’s fears about being left out were materializing, magnified by the fact that I couldn’t just go home. I had to stick it out, one way or another, find a way to be there while not completely being there. I watched Ben’s kids making camp and felt a nostalgia for a childhood I’d never experienced, this life of road trips and the outdoors that they so easily took to, which seemed to constantly reject me. They were a family unit with a long-established history. I felt like another species altogether.

I’d imagined that sometime along the hike I’d get to talk to each of the kids in turn, have a heart-to-heart. A little over two years earlier, I’d come into their lives like a storm, unsettled their family, pushed the boundaries of what they’d thought possible. They’d thought their parents would be together forever. Now they packed into a one-bedroom apartment half the week, sharing Ben’s bed as he took the couch.

I remember how jarring it was when my own parents were divorcing, like there was no sure footing at home. I stayed outside most days, where I could steady myself with the horizon line. The sunset on the Everglades was a kind of magic, milky pink and yellow clouds over a great expanse I imagined was infinite, a blank slate. Since my home had lost all semblance of order, I thought I might as well take to the wilderness. I dreamed of heading west, the direction of freedom.

Like all the white people before me who thought themselves pioneers, I’d neglected to consider the indigenous people who’d lived for hundreds of years in what I called the wild, who had a wholly different experience of frontiers and westward expansion: the Miccosukee. To them, freedom wasn’t some void beyond their reality, but something they fought for. Following the Indian Wars in the 1800s, most of the Creek tribes in Florida were moved to reservations out west. Except for about 100 Mikasuki-speaking Creeks, who hid in the Everglades in temporary camps. They lived like this for a century, resisting assimilation, until the early 1920s when they took part in the commerce along the Tamiami Trail. In the 1950s, one of the leaders of the tribe, Buffalo Tiger, visited Fidel Castro in Cuba, who accelerated the tribe’s international recognition as an independent country within the United States. If you drive around the Everglades, you’ll see the Miccosukee now live in modern homes, though most of them still have chickee huts in their backyards.

Lorraine Monteagut, left, with Ben, Morissey, Asher, and Bey Montgomery in Rockfish

Gap, experiencing the privilege of being outdoors willingly near an old settlers’ migration

route.

What is wild to one is home to another.

As I limped through Shenandoah National Park, I grappled with the concept of home. I’d decided to tough it out, walk through the pain. I used a walking stick I named Wandering Wanda, a thick one with a notch at the top I could put a lot of weight on. I had expected the trip to be physically hard, and though I hadn’t expected to be injured, once I got going, the pain wasn’t unbearable. It was the psychological challenge I hadn’t bargained for. I was raw. I fell behind the group, and the symbolism of that tore me open. Childhood feelings of loneliness rushed through me. Since I was alone on the trail so often, I took the opportunity to cry openly, sometimes loudly. If Ben or the kids heard me, they’d think I was crying because of my knee pain.

Out on the trail, I came to understand that I longed for a home I had yet to make. I’d spent so much time in my younger years constantly running from a home I’d deemed unstable. I was the first in my family to apply to college, and getting the acceptance letter from the University of Florida had been the happiest moment of my life. Since then, I had never settled, never stayed for longer than a couple years in one place.

I wonder if it’s in my blood, to keep moving, to never settle. We are a family of exiles and immigrants, after all, of people always on the edge of some frontier. Maybe it’s why the wilderness renders me so vulnerable. To my grandparents, the woods had human eyes and human dramas. The woods is where the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) lived, armed insurgents ready to kidnap their children. The woods are where Fidel Castro strengthened his army before striking their town and starting a revolution that pushed them from their homes forever. The woods aren’t a safe place. The woods aren’t for recreation. The woods are the difficult past.

There is a part of me that loves danger and seeks it out, that wants to delve into the dark recesses of the past and live there. When I was a teenager, I’d drive west on Tamiami Trail with my friends to this place we called the insane asylum, which has since been demolished. We’d take a left from Tamiami onto Krome Avenue, a spot that seemed so remote to us, back when it was just a two-lane road. One night, we pulled over at a broken section of the chain-link fence and cut the engine. The thick sound of outside took hold, the groan of reptiles alien to me and the constant shrill of the cicadas that forgot they were only supposed to explode upon humanity every seventeen years.

We stooped through the opening of the fence, fighting coarse grass and mangled bushes. The ground was surprisingly dry, and it cracked under us as we moved through. I tried to slow the sound under my feet, afraid to awaken something old and sleeping. When we got through, we came to a frontier of asphalt and marsh, what looked like a tarmac leading to squat buildings with long hallways, nothing but the river of grass beyond. We called it the insane asylum because we were teenagers and hungry for drama. We smoked pot and tagged our names on the walls and dared each other to walk the broken halls.

I later found out that it was a missile base constructed around the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, a remnant of the Cold War. In the 1980s, it was converted into a detention center to process the immigrants from the Mariel boatlift, the huge sanctioned emigration of Cubans from Mariel Harbor to the United States. Today, the original buildings are gone and all that’s left are concrete pads in a far corner of the Krome Detention Center, which now processes immigrants from all over the world and which has a long history of detainee abuse.

When I think of wilderness, I think of places like this, of unexpected human objects suspended in nature, of humans in hiding or imprisoned. I think of the migrants who worked the strawberry fields of my childhood, who lived in temporary camps in a place I thought was all wild, who still live there, who live all over this country, invisible, working for our food system in a sort of indentured servitude. I think of the migrants we don’t let in, those people who walked because they had no choice, who carried their children and somehow moved hundreds and thousands of miles through Central America, through Mexico, and who are now separated from their children at the U.S.–Mexico border, put in cages, called animals by our president.

When I think of wilderness, I remember the look of fear in the eyes of the hundreds of Haitian refugees who ran onto the Rickenbacker Causeway in 2002 as I was driving home from high school, who tried to get into my car. How many times I have returned to that moment in my memory and hit the unlock button, driven them to Little Haiti to save them from being taken to Krome, to prevent their inevitable deportation back to places they can no longer call home.

I’d like to think that I was crying for all of these people during my hike in the Shenandoah. But these are associations I can make now, from the safety of my house, fully back in civilization. No, long hard hikes in remote places have a way of exposing what’s most tender and personal. I was crying selfishly. I was crying for home—my home, or the ideal of home that I had not yet achieved.

By the last night, my knee pain was minimal and I’d gotten all my crying out. Over the couple of weeks of hiking together, Ben and the kids and I felt like a unit, like we’d gone through something important together. I hadn’t had the private conversations I’d imagined, but we’d bonded quietly over shared tasks in close quarters. As we made our last camp at Sam Moore Shelter, we played our made-up games and challenged each other to a pushup contest. I maxed out at fifteen before my arms buckled and I fell to the ground, tired, laughing.

That night, there was a torrential downpour. Ben couldn’t just sit in the tent this time. He spent a couple hours digging trenches around our tents to keep the water from getting in. It was a miracle we stayed dry. The next day, when we got to Harpers Ferry and the end of our journey, we picked up a copy of the Washington Post, which reported that the area had received about a month of rain in one hour, causing flash flooding. Major roads became rivers, sinkholes opened up, people had to abandon their cars and walk. And we slept outside! we bragged. We’d made it through our epic trip, intense storms and all.

As the effects of climate change worsen and economic and political pressures increase worldwide, some scientists project that we will see a forced mass migration of millions of people by the end of the century. What we consider wilderness and what we consider civilization will become moving targets in this country, as wildfires rage in the west, hurricanes emerge in the Gulf, snowstorms descend from the north. Change will be the only constant, and new frontiers we can’t yet imagine will emerge.

I sit and write this on the back deck of the home I’ve been slowly making for myself. From here, I watch the colony of bees I’ve set up toward the back of the yard. The bees dart out into their version of the wild—the patch of flowers next to someone’s mailbox, the median on a busy highway—and they return to their version of civilization laden with pollen. I don’t mow or use pesticides, and I’ve noticed the wild returning to my little plot of land: bugs I’ve never seen, medicinal flowers, vines of tomatoes in the drainage ditch. Wilderness is all around and deeply personal, not something to be discovered “out there.”

If we are to successfully protect the wild spaces of this world that bring us so close to the marrow of life, we have to start with ourselves. We must each nurture the wild self, the vulnerable self who is always seeking home in this world, who faces hardships but does not quit, who adapts in hopes of a better life. And even as we make room for ourselves in this exploration, we must make room for others. We have always been a beacon of safety, a country of immigrants. We must continue to have empathy for those who seek asylum and invite them into our family.

Just as surely as there will be storms, there will be human migration, and it’s time we acknowledged that human movement is also natural. It might seem to us now that there was more room back in the 1700s, but the concepts of the American frontier and wilderness were even then largely imaginary, a matter of perception. Now, we have the opportunity to consciously redefine our next frontier to nurture all life forms. It is a door between the wild and the civilized that is forever shifting so that we may protect what’s important to us and make room for more, be it flora, fauna, or human. There is space yet for us all.

Lorraine Monteagut is a writer, designer, and communication PhD who lives in Tampa, Florida. This is her first major feature article.

Editor’s note: After the Waterman Fund’s essay contest committee and I chose this piece as the winner for 2020, we then learned the author’s name and realized that her companion in this story is Ben Montgomery, a writer whose essay about the same two daughters and son on an earlier hike appeared in Appalachia’s Summer/ Fall 2019 issue. We loved Monteagut’s perspective on her life, on American attitudes about the outdoors, and on her experiences with a family we felt we’d gotten to know a little bit.

Just days after Monteagut completed this essay, in March 2020, Montgomery’s son, Bey, died. He was 11 and had completed 405 miles of the Appalachian Trail. Monteagut dedicates this piece to him. We at the journal continue to grieve this loss, honor Bey’s memory, and wish the family well.